ICI Viewpoints

The SEC’s Liquidity Proposal Is Arbitrary and Harmful to Investors

Open-end long-term mutual funds (“funds”) have a long history of successfully managing liquidity, enabling them to meet shareholder redemptions in a timely manner while pursuing their investment objectives. Over the past four decades, 99.94% of these funds have met redemptions, including every single fund during the 2008 global financial crisis and the 2020 dash for cash.

Despite this sterling track record, the SEC is worried about funds’ ability to withstand periods of market stress, going so far as to propose a dramatic overhaul of its liquidity risk management rule for funds—stock, bond, and hybrid funds alike.

If adopted, however, the proposed rule amendments would saddle fund investors with higher costs, unexpected tax bills, and lower returns. They would also make some of the most popular and liquid funds in the world, such as S&P 500 index funds, unviable when they reach a certain size.

Liquidity Management Rules: Current and Proposed

Currently, the SEC requires funds to classify each portfolio investment into one of four buckets—highly liquid, moderately liquid, less liquid, and illiquid—at least monthly. This bucketing process requires funds to determine how many days it would take them to sell or convert to cash a reasonably anticipated trade size of each investment, factoring in the potential impact on the investment’s market value as well as other considerations.[1] Critically, the rule limits the portion of a fund’s assets than it can hold in its illiquid bucket to 15%.

Among other proposed changes to the underlying bucketing requirements, the SEC wants to replace the reasonably anticipated trade size with an extreme required trade size assumption: a pro rata sale of 10% of a fund’s assets on any given day.[2] Collectively, the changes could force funds to classify more than 15% of their assets as illiquid, thus violating the rule’s limit.

Funds that exceed the limit would have few options to return to compliance, each of which, as shown below, would harm their shareholders.

Figure 1

Few Options to Comply with Rule—None Are Good for Investors

| Compliance Option | Likely Consequences for Investors |

|

Increase allocation to cash or US Treasuries |

Lower returns over time Unexpected capital gains taxes from sales of portfolio investments |

|

Cap fund size1 or split fund into smaller clone funds2 |

Reduced economies of scale Higher expense ratios Investor confusion3 Unexpected capital gains taxes4 |

|

Change the fund’s investment objectives and strategy5 |

Lower expected returns over time Fewer types of funds Reduced choice for investors |

1To avoid becoming large enough to breach the illiquid limit.

2Despite holding in aggregate the exact same assets as their larger predecessor fund, smaller clone funds would be deemed more liquid simply because of the importance of the 10% trade size assumption.

3When their ongoing purchases for a given fund are rejected or redirected to a clone fund.

4When investors exchange shares from larger fund for those of the smaller clone fund, they would owe tax on gains on the old shares at the time of the restructuring.

5Funds may eschew certain asset classes that could be labeled illiquid under the proposal.

Penalizing Larger and More Concentrated Funds

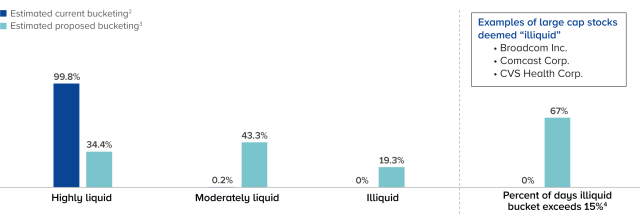

The SEC’s 10% trade size assumption will penalize large and moderately sized funds that have more concentrated portfolios by creating a distorted view of these funds’ liquidity risks, according to ICI research.[3]

For example, an actively managed US-focused large-cap equity fund, which holds some of the deepest and most liquid securities in the world, would go from having nearly all its stocks classified as highly liquid to regularly exceeding the 15% cap.[4] And some of the fund’s individual holdings—Broadcom, Comcast, and CVS, for example—would be deemed illiquid despite having been among the 100 most heavily traded stocks in the S&P 500 index (Figure 2).

Over the past three years, the fund would have breached the limit on two-thirds of trading days. Even S&P 500 and other equity index funds, which are some of the most popular and liquid funds in the marketplace, would confront this problem when they reach a certain size.[5]

Figure 2

Proposed Bucketing Scheme Can Create a Distorted View of a Fund’s Liquidity Risks

Proposed bucketing scheme1 conducted on an actively managed US-focused large-cap equity mutual fund with between $125 billion and $175 billion in assets

1Bucketing exercise was conducted daily on US equity holdings from the fund’s quarterly public N-PORT holdings from late 2019 to early 2023.

2Current bucketing was estimated with trade size proxied by the fund’s March 2020 flows and the proposed ADTV requirements. For convenience, the less liquid bucket was combined with the illiquid bucket.

3Proposed bucketing was estimated using the proposed 10% trade size, ADTV requirements, day counting convention, and loss of less liquid bucket.

4Fund had 805 trading days in the analysis.

Source: ICI calculations of SEC Form N-PORT, Refinitiv, and Morningstar Direct data

An Arbitrary Determination

How did the SEC arrive at the 10% assumption at the heart of its bucketing changes?

In what was effectively a three-step method based on funds’ historical flows,[6] the SEC determined the figure by mixing together all funds’ flows and pulling out a rare weekly outflow level of 6.6%, rounding that figure up to 10%, then arbitrarily turning that weekly number into an extremely unlikely level of daily outflows (Figure 3).[7]

Astoundingly, the SEC proposal would mandate that every fund assess its liquidity using the 10% trade size every day, even though a 10% daily outflow, for most funds, is more improbable than a black swan event.

Figure 3

SEC Proposal Arbitrarily Converts a 6.6% Weekly Outflow into a 10% Daily Outflow

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | |

| Percentage outflow | Weekly ≥ 6.6% | Weekly ≥ 10.0% | Daily ≥ 10.0% |

| Probability of seeing these flows | 1% | 0.5% | 0.14% |

| General likelihood | rare | very rare | extremely rare |

Sources: SEC proposal and ICI calculations of Morningstar Direct data

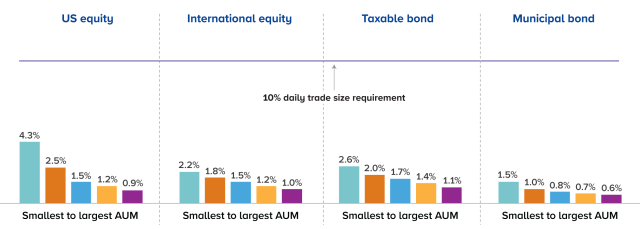

Put simply, there is no single assumed trade size number that makes sense for all funds at all times. Outflow levels vary widely by fund size, portfolio characteristics, and other factors. One consistency, however, is that across all fund sizes and asset classes, the top percentile of daily outflows—the SEC’s own proxy for extreme outflows—which includes periods of market stress, is significantly smaller than the 10% daily trade size assumed by the SEC (Figure 4).

Figure 4

One-Size-Fits-All Approach for Required Trade Size Doesn’t Work

Outflows at first percentile of daily pooled flow distribution by asset class and fund size quintiles

Source: ICI calculations of Morningstar Direct data

A Fundamentally Flawed Design

ICI does not object to considering stress in setting trade size assumptions, provided that the determination is fund specific. To that end, we recommend that the SEC allow funds to continue determining their trading size figures based on their own liquidity risk factors.

Given the liquidity rule’s architecture, this poorly considered, one-size-fits-all trading requirement can cause serious harm. Adoption of the rule would trade away the viability of many funds and hurt the millions of investors who depend on them.

Notes

[1] Currently, this “reasonably anticipated trade size” determination is based on a fund-specific liquidity risk assessment, which generally yields numbers well below the proposed 10% mandated figure.

[2] In addition to changing the size assumption, the proposal would: (i) impose a minimum value impact requirement by defining “significantly changing the market value of an investment” to include precise numerical standards; (iii) eliminate the asset class classification method; (iii) eliminate the “less liquid” bucket, reducing the number of buckets from four to three, and change the definitions for the remaining three buckets to narrow the “highly liquid” bucket and expand the “illiquid” bucket; (iv) change the method for counting days in a way that shaves a day off the highly liquid and illiquid buckets; and (v) require daily bucketing. For more detail on the current and proposed rule’s requirements, see ICI’s comment letter on the proposal.

[3] We assessed the impact by assuming the proposed: 10% required trade size assumption; value impact standard for exchange-traded investments (a fund can sell at most 20% of a stock’s 20-day trailing average daily trading volume (ADTV) in a day without significant price impact); day counting convention (i.e., the day of the assessment is “Day 1” rather than “Day 0”); and elimination of the “less liquid” bucket and expansion of the “illiquid” bucket. We categorized each stock held by the fund into the proposed buckets based on the magnitude of the 10% share of the stock relative to the 20% ADTV limit. If the 10% share of the stock represented 20% or less of the stock’s 20-day trailing ADTV, then the stock was classified entirely as highly liquid. If the 10% share was greater than 20% but less than or equal to 60% of 20-day trailing ADTV, the stock was classified entirely as moderately illiquid. Finally, if the 10% share was greater than 60% of 20-day trailing ADTV, the stock was classified entirely as illiquid. The analysis further assumes that the stocks in question cash settle on a “T+2” basis, and consistent with the current and proposed bucketing framework, stocks cannot be “split” across buckets (e.g., if the fund cannot fully dispose of the 10% position within three trading days, the full position is classified as “illiquid,” notwithstanding the ability to dispose of a portion of the holding on Days 1 through 3).

[4] Other examples are shown in Figure 3.4 of Appendix A in ICI’s comment letter on the proposal.

[5] See Figure 3.7 of Appendix A in ICI’s comment letter on the proposal.

[6] The historical flow data that the SEC relies on has numerous data errors and limitations that the SEC does not control for. Failure to adjust for these data issues overstate the magnitude of funds’ outflows and as a result could materially impact the SEC’s analysis. See pages 38–39 of Appendix A in ICI’s comment letter on the proposal.

[7] The SEC computed weekly flows (expressed as a percentage of assets) for each mutual fund over the period 2009 to 2021, mixed all the funds’ flows together, and then ranked them from smallest to largest. In this distribution, “smallest” represents the biggest weekly outflows and “largest” represents the biggest weekly inflows. Because the SEC wanted to proxy for “extreme outflows” that funds might experience in stressed conditions, they focused on the part of the distribution with the largest weekly outflows and selected the weekly outflow that had at most a 1% chance of occurring for any fund in any week (6.6%). The SEC’s own analysis of historical flows shows that daily outflows, even at an extreme level, are significantly smaller than 10%. The SEC finds that the daily outflow that has at most a 1% chance of occurring for any fund on any day is only 1.6%—well below the SEC’s 10% assumption.

Shelly Antoniewicz is the Deputy Chief Economist at ICI.

Matt Thornton is an Associate General Counsel, Securities Regulation at ICI.